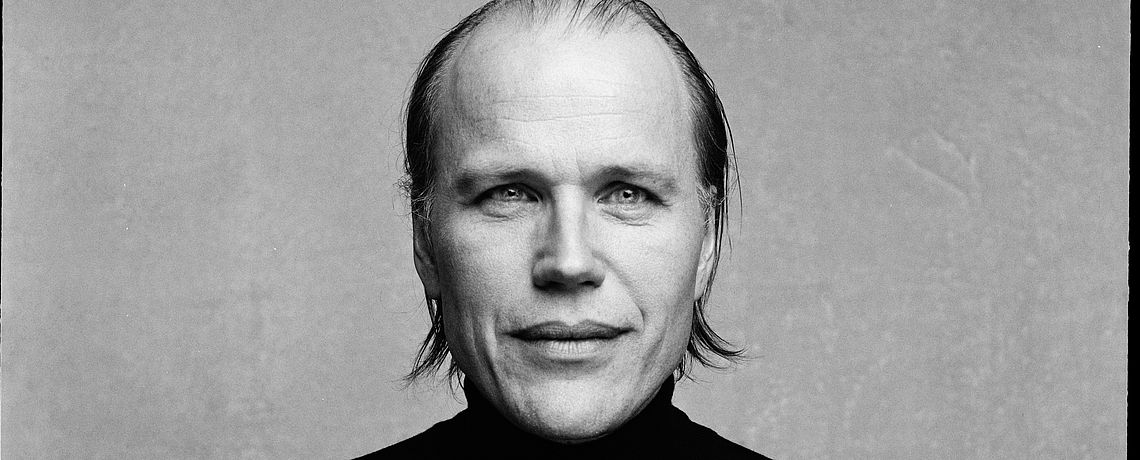

Christian Kjellvander

"Hold Your Love Still" (release date: 3 November 2023)

“I want to give you this and ask for nothing in return.”

Naked but for a soft blanket of reverb, Christian Kjellvander’s tender voice invites us into his latest creation, the swooning ‘Hold Your Love Still’. His first solo album since 2020’s ‘About Love And Loving Again’ finds the Swedish troubadour in a reflective mood, exploring the difficulties of an honest life amid the entanglement of capitalism, and imploring us to nurture that faltering hope for a better tomorrow. Though he’s grappling with existential and environmental tensions, Kjellvander strides from stoicism to optimism, augmenting his trademark minor melancholy with soaring major compositions, each concise, precise and considered – a conscious turn towards song from the freeform expressions of recent collaborations. Rich in natural imagery, understated poetry and an infectious empathy, with meaning imbued in every line, this is the work of an accomplished songwriter at his most vital.

For Christian, the love of the album title is a state of energy or a concentration of feelings, an ineffable quality which he sometimes feels is missing in modern society. Dewy opener “Western Hemisphere” affirms that everything we need is already in our grasp; we just need to stay still long enough to see it. A grounded celebration of the power of nature, this is a reminder that the long grass has more beauty than the manicured lawn. Our preoccupation with perfection also informs “Notes From The Drive Between Simat and Alcoi”, a travelogue from South-Eastern Spain inspired by breathtaking valleys, a Cistercian monastery and the comforting distortion of a well used sound system. Recalling a gig in Alcoi, a town famed for its labour movement even as the world’s pickets fall hushed, Kjellvander rejoices in the jagged countryside, weathered stone buildings and buzzing speakers, protesting the straight lines and clean sound of our commercialised existence as the song builds from ballad to anthem.

“Baleen Whale” compares the accumulated weight of watching the news or internalising the troubles of others with a filter-feeding whale, which eventually finds itself beached. Set to the steady rhythm of rumbling bass and brush drums, delicate piano and sombre strings create a melancholy backing for Kjellvander’s tale until a sudden swell of hopeful chords carries the chorus aloft. Four songs in and Christian fashions his love into a love song, examining intimacy and vulnerability on the gorgeous “Terns Took Turns”. Not only does he capture the moment of surrender to overwhelming affection, but also the kind of closeness which allows communication without words.

The cinematic and stomping “Disgust For The Poor” delivers a dissection of capitalism, consumerism and continued colonialism and questions whether we can do more to make a difference while enjoying all the comforts of an unfair system. Intoxicating and imagistic “On Wine And Jesus Christ” sees Kjellvander realise a longstanding desire to explore his relationship with alcohol, recalling the ways in which he’s used it, and it’s used him, on his way to a healthy enjoyment of the holy feeling it can bring.

The sparse and stately “We Are Gathered” stretches its languid groove over nine minutes, weighing the balance of the album’s thematic thrust and marrying accountability with optimism. As the piece spirals out into a mostly instrumental ending, a delicate solo floats above the solemn groove before boldly untethering into a crescendo of rolling snare and staccato guitar. The optimism extends to the pastoral and placid psychedelia of closer “Dream 2066”, a reassuring vision of a possible future free from climate disaster and the clutches of capitalism. Kjellvander’s comforting croon leaves us with a lasting message of the power of togetherness. A fitting finale to a faultless LP, this is an affirmation that it’s not too late to make a change, and that some of us might have come to that realisation earlier than others.

Deutscher Pressetext

“I want to give you this and ask for nothing in return.”

Von einem zarten Schleier des Halls umgeben, eröffnet uns Christian Kjellvander mit seiner sanften Stimme die Tür zu seinem neuesten Werk "Hold Your Love Still“ – sein erstes Soloalbum seit "About Love And Loving Again" aus dem Jahr 2020. In dieser Schaffensphase zeigt sich Kjellvander von seiner reflektierenden Seite und erkundet die Herausforderungen einer aufrichtigen Lebensführung, verstrickt in den komplexen Einflüssen des Kapitalismus. Gleichzeitig fordert er uns dazu auf, die Hoffnung auf eine bessere Zukunft nicht zu verlieren.

Das Album beschäftigt sich mit existenziellen und umweltbedingten Spannungen, wandelt jedoch gekonnt zwischen Stoizismus und Optimismus. Er bereichert seine charakteristische melancholische Stimmung mit schwebenden Kompositionen in Dur, die jeden Song zu einem tiefgründigen Erlebnis machen. Jeder Song ist präzise und durchdacht – im Gegensatz zu den musikalischen Grenzüberschreitungen, die für seine letzten Werke prägend waren, vollzieht er nun eine bewusste Hinwendung zum Song. Die Texte sind voller natürlicher Bilder, subtiler Poesie und faszinierender Empathie. Dies ist die Arbeit eines erfahrenen Songwriters, der sich in Höchstform präsentiert.

Die Liebe, von der im Albumtitel die Rede ist, ist ein Zustand der Energie bzw. eine Konzentration von Gefühlen, eine schwer zu beschreibende Qualität jedenfalls, die er gelegentlich in unserer modernen Gesellschaft vermisst. Das erfrischende Eröffnungsstück "Western Hemisphere" bestätigt, dass alles, was wir brauchen, bereits in unserer Nähe liegt; wir müssen nur lange genug stillhalten, um es zu erkennen. Das Stück feiert die Kraft der Natur und erinnert uns daran, dass das hohe Gras mehr Schönheit besitzt als der noch so sorgfältig gepflegte Rasen. Auch "Notes From The Drive Between Simat and Alcoi“ hat das in unserer Gesellschaft so verbreitete Streben nach Perfektion zum Thema. Es ist ein Reisebericht aus dem südöstlichen Spanien, inspiriert von atemberaubenden Tälern, einem Zisterzienserkloster und der beruhigenden Verzerrung eines ziemlich maroden Sound-Systems. Darin erinnert Kjellvander sich an einen Auftritt in Alcoi, einer Stadt, die in den Anfängen der Arbeiterbewegung im 19. Jahrhundert eine zentrale Rolle gespielt hat, auch wenn Streikposten ihre Stimme heutzutage nur noch im Flüsterton erheben. Kjellvander bringt seine Freude an zerklüfteten Landschaften, verwittertern Gemäuern und brummenden Lautsprechern zum Ausdruck und äußert zugleich seinen Protest gegen die schnurgeraden Linien und den sauberen Sound unserer kommerzialisierten Existenz. Unterdessen entwickelt sich das Stück von der Ballade zur Hymne.

In dem Song "Baleen Whale" geht es um die Belastung durch die ständige Überflutung mit Nachrichten oder auch die fehlende Abgrenzung gegenüber den Problemen anderer Menschen. Christian zieht daher den Vergleich zu einem Wal, der unablässig Nahrung durch seine Barten filtert und schließlich strandet. Ein rumpelnder Bass und Schlagzeugbesen bilden das rhythmische Gerüst, während das zarte Piano und düstere Streicher einen melancholischen Hintergrund für Kjellvanders Geschichte bilden, bis schließlich ein unerwarteter Schwall aus hoffnungsträchtigen Akkorden den Refrain in ungeahnte Höhen hebt.

Im vierten Song des Albums, dem wunderschönen „Terns Took Turns“, webt Christian seine eigene Liebe in ein Liebeslied ein, in dem er sich mit Intimität und Verletzlichkeit auseinandersetzt. Er fängt in diesem Stück nicht nur den Moment der Hingabe an das überwältigende Gefühl der Zuneigung ein, sondern auch jene Nähe, die eine Kommunikation ohne Worte erst möglich macht.

Das sehr plastische, von einem stampfenden Rhythmus begleitete „Disgust For The Poor“ liefert eine schmerzhaft präzise Analyse des Kapitalismus, des Konsumismus und des fortgesetzten Kolonialismus. Gleichzeitig stellt es die Frage, ob wir ein ungerechtes System wirklich verändern können, während wir gleichzeitig all die Annehmlichkeiten genießen, die es uns bietet. In dem berauschenden und phantasievollen „On Wine And Jesus Christ“ verwirklicht Kjellvander dann ein lang gehegtes Vorhaben und erforscht seine Beziehung zum Alkohol, erinnert sich daran, wie er den Alkohol und wie dieser ihn benutzt hat. Ist es möglich, Alkohol zu genießen, ohne gleichzeitig seinen Gefährdungen zu erliegen?

Das Album erreicht seinen Höhepunkt in dem epischen und fesselnden Track "We Are Gathered", der eine neunminütige Reise darstellt, die die Albumthematik geschickt mit Verantwortungsbewusstsein und Optimismus verbindet. Die Musik entführt den Hörer in einen hypnotischen Zustand, während die Melodien und Klänge sich zu einem beeindruckenden Crescendo entwickeln.

Mit dem abschließenden Song "Dream 2066" präsentiert uns Christian Kjellvander eine beruhigende Vision einer möglichen Zukunft, die frei von Klimakatastrophen und den Fesseln des Kapitalismus ist. Seine tröstliche Stimme hinterlässt eine bleibende Botschaft über die Macht der Gemeinschaft und des Zusammenhalts.